This post was originally featured on the Field Service USA blog.

This is the third post in a three-part series exploring servitization. The first post dove into the underlying problem that begat the need for servitization, and the second post dove into what servitization is and the impacts to manufacturers (OEMs) and their customers. This post will explore the infrastructure OEMs need to build in their organizations in order to bring servitization to life.

We’ll start with the implications of servitization on financial infrastructure, then dive into org structure, and lastly technology tools.

At the most basic level, servitization is about growing long term, recurring revenue while reducing short term business risk. More specifically, this is about moving from just selling capital equipment to selling equipment and services on top of that to maximize the value that customers can extract from a given piece of equipment. In the most extreme servitization models, this may even involve subsidizing capital equipment sales with service revenue, incurring a short term cash hit for even more long term recurring revenue.

The move to servitization has substantial impacts on cash flows. Traditional OEM cash flows tend to revolve around end-of-quarter as capital equipment purchases can take significant time to approve and typically revolve around quarterly budget meetings. Note that the numbers below are for a hypothetical OEM.

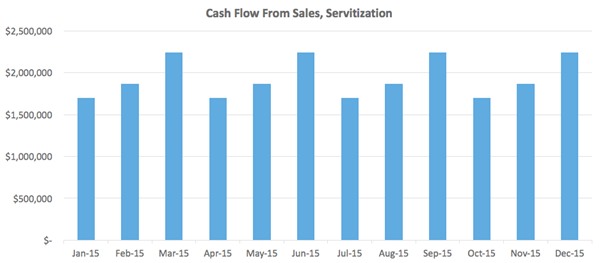

This stands in stark contrast to a more typical servitization based cash flow model, where revenue between equipment sales and service blurs and normalizes.

Although there is still seasonality in the servitization model, the month-over-month cash flow changes are tempered significantly. This reduces cash flow risk to the OEM, normalizes customer payments for the customer, and presents an opportunity for greater long term revenue capture per customer. Everyone wins.

Although every organization is different, it’s possible to paint broad strokes on the management structure needed to deliver servitized performance. The key to delivering servitized product delivery is organizational alignment. The lines between sales and service must blur: sales teams must learn, appreciate, and sell the value of service and customer-value-extraction. Service, on the other hand, must recognize that the company’s financial performance will depend on their ability to execute and ensure that customers extract the expected value from the OEM’s equipment.

If service fails, revenue will be negatively impacted. As a result of this interdependence, sales and service organizations need to work more closely together. These two organizations should report into a single unified head - with a title such as VP of Customer Success - whose two largest components of variable comp should be service delivery and sales, in that order. It must be clear from the top down that customer service is king.

Lastly, OEMs will need a new set of tools to succeed in a servitization world. Traditional field service management software will not be enough. Servitization is about customer service; as such, OEMs will need new tools to more effectively engage and support their customers. On demand support tools such as those offered by Pristine will become ever more important. So will tools that empower customers to diagnose and repair equipment on their own. These tools will become mission critical as OEMs won’t be paid if their equipment isn’t working as advertised. OEMs must find and implement the right tools so that their customers can service equipment on demand with OEM support and guidance.